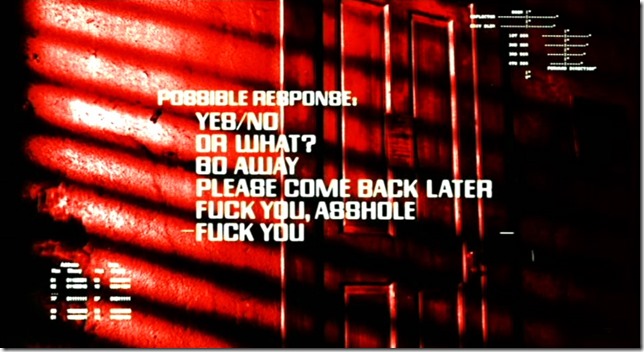

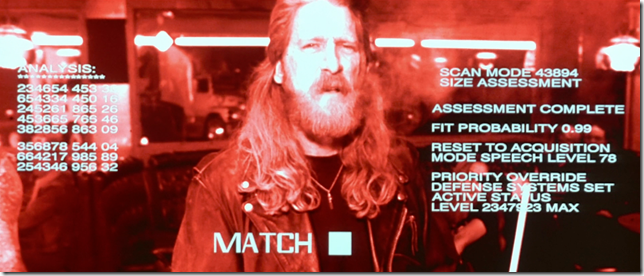

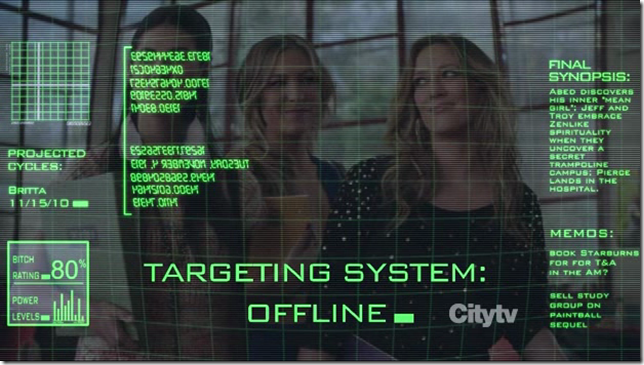

James Cameron’s film The Terminator introduced an interesting visual effect that allowed audiences to get inside the head and behind the eyes of the eponymous cyborg. What came to be called terminator vision is now a staple of science fiction movies from Robocop to Iron Man. Prior to The Terminator, however, the only similar robot-centric perspective shot seems to have been in the 1973 Yul Brynner thriller Westworld. Terminator vision is basically a scene filmed from the T-800’s point-of-view. What makes the terminator vision point-of-view style special is that the camera’s view is overlaid with informatics concerning background data, potential dialog choices, and threat assessments.

But does this tell us anything about how computers actually see the world? With the suspension of disbelief typically required to enjoy science fiction, we can accept that a cyborg from the future would need to identify threats and then have contingency plans in case the threat exceeds a certain threshold. In the same way, it makes sense that a cyborg would perform visual scans and analysis of the objects around him. What makes less sense is why a computer would need an internal display readout. Why does the computer that performs this analysis need to present the data back to itself to read on its own eyeballs?

Looked at from another way, we might wonder how the T-800 processes the images and informatics it is displaying to itself inside the theater of its own mind. Is there yet another terminator inside the head of the T-800 that takes in this image and processes it? Does the inner terminator then redisplay all of this information to yet another terminator inside its own head – an inner-inner terminator? Does this epiphenomenal reflection and redisplaying of information go on ad infinitum? Or does it make more sense to simply reject the whole notion of a machine examining and reflecting on its own visual processing?

I don’t mean to set up terminator vision as a straw man in this way just so I can knock it down. Where terminator vision falls somewhat short in showing us how computers see the world, it excels in teaching us about how we human beings see computers. Terminator vision is so effective as a story telling trope because it fills in for something that cannot exist. Computers take in data, follow their programming, perform operations and return results. They do not think, as such. They are on the far side of an uncanny valley, performing operations we might perform but more quickly and without hesitation. Because of this, we find it reassuring to imagine that computers deliberate in the same way we do. It gives us pleasure to project our own thinking processes onto them. Far from being jarring, seeing dialog options appear on Arnold Schwartzenegger’s inner vidscreen like a 1990’s text-based computer game is comforting because it paves over the uncanny valley between humans and machines.

Maybe it’s for debugging for the T-800’s engineers? There has to be an internal readout/logging system along with image processing results.