“Plurality should not be posited without necessity.” — William of Occam

I added an extra hour to my commute this morning by taking a shortcut. The pursuit of shortcuts is a common pastime in Atlanta — and no doubt in most metropolitan areas. My regular path to work involves taking the Ronald Reagan Highway to Interstate 85, and then the 85 to the 285 until I arrive at the northern perimeter. Nothing could be simpler, and if it weren’t for all the other cars, it would be a really wonderful drive. But I can’t help feeling that there is a better way to get to my destination, so I head off on my own through the royal road known as “surface streets”.

Cautionary tales like Little Red Riding Hood should tell us all we need to know about taking the path less traveled, yet that has made no difference to me. Secret routes along surface streets (shortcuts are always a secret of some kind) generally begin with finding a road that more or less turns the nose of one’s car in the direction of one’s job. This doesn’t last for long, however. Instead one begins making various turns, right, left, right, left, in an asymptotic route toward one’s destination.

There are various rules regarding which turns to make, typically involving avoiding various well-known bottlenecks, such as schools and roadwork, avoiding lights, and of course avoiding left turns. Colleagues and friends are always anxious to tell me about the secret routes they have discovered. One drew me complex maps laying out the route she has been refining over the past year, with landmarks where she couldn’t remember the street names, and general impressions about the neighborhoods she drove through when she couldn’t recall any landmarks. This happened to be the route that made me tardy this morning.

When I told her what had happened to me, the colleague who had drawn me the map apologized for not telling me about a new side-route off of the main route she had recently found (yes, secret routes beget more secret routes) that would have shaved an additional three minutes off of my drive. Surface streets are the Ptolemaic epicycles of the modern world.

A friend with whom I sometimes commute has a GPS navigation system on his dashboard, which changes the secret route depending on current road conditions. This often leads us down narrow residential roads that no one else would dream of taking since they wouldn’t know if the road leads to a dead-end or not — but the GPS system knows, of course. We are a bit slavish about following the advice of the GPS, even when it tells us to turn the trunk of the car toward work and the nose toward the horizon. One time we drove along a goat path to Macon, Georgia on the advice of the GPS system in order to avoid an accident on S. North Peachtree Road Blvd.

All this is made much more difficult, of course, due to the strange space-time characteristics of Atlanta which cause two right turns to always take you back to your starting point and two left turns to always dump you into the parking lot of either a Baptist church or a mall.

Various reasons are offered to explain why the Copernican model of the solar system came to replace the Ptolemaic model, including a growing resentment of the Aristotelian system championed by the Roman Catholic Church, resentment against the Roman Catholic Church itself, and a growing revolutionary humanism that wanted to see the Earth and its inhabitants in motion rather than static. My favorite, however, is the notion that the principle of parsimony was the deciding factor, and that at a certain point people came to realize that the simplicity, rather than complexity, is the true hallmark of scientific explanation.

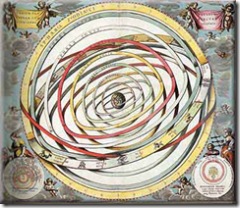

The Ptolemaic system, which places the earth at the center of the universe, with the Sun, planets and heavenly sphere revolving around it, was not able to explain the observed motions of the planets satisfactorily. We know today was due to both having the wrong body placed in the center of the model, as well as insisting on the primacy of circular motion rather than elliptical route the planets actually take.

In particular, Ptolemy was unable to explain the occasionally observed retrogression of the planets, during which these travelers appear to slow down and then go into reverse during their progression through the sky, without resorting to the artifice of epicycles, or mini circles, which the planets would follow even as they were also following their main circular routes through the sky. Imagine a ferris wheel on which the chairs do more than hang on their fulcrums; they also do loop-de-loops as they move along with the main wheel. In Ptolemy’s system, not only would the planets travel along epicycles that traveled on the main planetary paths, but sometimes the epicycles would have their own epicycles, and these would beget additional epicycles. In the end, Ptolemy required 40 epicycles to explain all the observed motions of the planets.

Copernicus sought to show that, even if his model did not necessarily exceed the accuracy of Ptolemy’s system, he was nevertheless able to get rid of many of these epicycles simply by positing the Sun at the center of the universe rather than the Earth. At that moment in history simplicity, rather than accuracy per se, became the guiding principle in science. It is a principle with far reaching ramifications. Rather than the complex systems of Aristotelian philosophy, with various qualifications and commentaries, the goal of science (in my simplified tale) became the pursuit of simple formulas that would capture the mysteries of the universe. Whereas Galileo wrote that the book of the universe is written in mathematics, what he really meant is that it is written in a very condensed mathematics and is a very short book, brought down to a level that mere humans can at last contain in their finite minds.

The notion of simplicity is germane not only to astronomy, but also to design. The success of Apple’s IPod is due not to the many features it offers, but rather to the realization that what people want from their devices is only a small set of features done extremely well. Simplicity is the manner in which we make notions acceptable and conformable to the human mind. Why is it that one of the key techniques in legal argumentation is to take a complex notion and reframe it in a metaphor or catchphrase that will resonate with the jurists? The phrase “If the glove doesn’t fit, you must acquit” was, though bad poetry, rather excellent strategy. “Separate but not equal” has resonated and guided the American conscience for fifty years. Joe Camel, for whatever inexplicable reasons, has been shown to be an effective instrument of death. The paths of the mind are myriad and dark.

Taking a fresh look at the surface streets I have been traveling along, I am beginning to suspect that they do not really save me all that much time. And even if they do shave a few minutes off my drive, I’m not sure the intricacies of my Byzantine journey are worth all the trouble. So tomorrow I will return to the safe path, the well known path — along the Ronald Reagan, down the 85, across the top of the 285. It is simplicity itself.

Yet I know that the draw of surface streets will continue to tug at me on a daily basis, and I fear that in a moment of weakness, while caught behind an SUV or big rig, I may veer off my intended path. In order to increase the accuracy of his system, even Copernicus was led in the end to add epicycles, and epicycles upon epicycles, to his model of the universe, and by the last pages of On the Revolution of the Heavenly Bodies found himself juggling a total of 48 epicycles — 8 more than Ptolemy had.

Oh, man. The Hell that is the Atlanta Commute. I’m a much simpler soul, so I always make sure to live less than ten miles from my office — with a route that avoids all highways. Probably why my hair just started graying in my late forties.

Great post.

Ahhh. I envy you, Beth.

love your blog beth

great post, those pluralitas!