In the previous post I wrote about “experience.” Here I’d like to talk about the “emerging.”

There are two quotations everyone who loves technology or suffers under the burden of technology should be familiar with. The first is Arthur C. Clarke’s quote about technology and magic. The other is William Gibson’s quote about the dissemination of technology. It is the latter quote I am initially concerned with here.

The future has arrived – it’s just not evenly distributed yet.

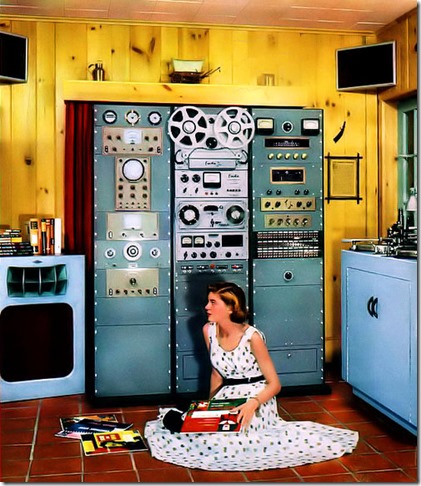

The statement may be intended to describe the sort of life I live. I try to keep on top of new technologies and figure out what will be hitting markets in a year, in two years, in five years. I do this out of the sheer joy of it but also – perhaps to justify this occupation – in order to adjust my career and my skills to get ready for these shifts. As I write this, I have about fifteen depth sensors of different makes, including five versions of the Kinect, sitting in boxes under a table to my left. I have three webcams pointing at me and an IR reader fifteen inches from my face attached to an Oculus Rift. I’m also surrounded by mysterious wires, soldering equipment and various IoT gadgets that constantly get misplaced because they are so small. Finally, I have about five moleskine notebooks and an indefinite number of sticky pads on which I jot down ideas and appointments. As emerging technology is disseminated from wherever it is this stuff comes from – probably somewhere in Shenzhen, China – I make a point of getting it a little before other people do.

But the Gibson quote could just as easily describe the way technology first catches on in certain communities – hipsters in New York and San Francisco – then goes mainstream in the first world and then finally hits the after markets globally. Emerging markets are often the last to receive emerging technologies, interestingly. When they do, however, they are transformative and spread rapidly.

Or it could simply describe the anxiety gadget lovers face when they think someone else has gotten the newest device before they have, the fear that the future has arrived for others but not for them. In this way, social media has become a boon to the distressed broadcast industry by providing a reason to see a new TV episode live before it is ruined by your Facebook friends. It is about making the future a personal experience, rather than a communal one, for a moment so that your opinions and observations and humorous quips about it — for that oh-so-brief period of time — are truly yours and original. No one likes to discover that they are the fifth person responding to a Facebook post, the tenth on instagram, or the 100th on twitter to make the same droll comment.

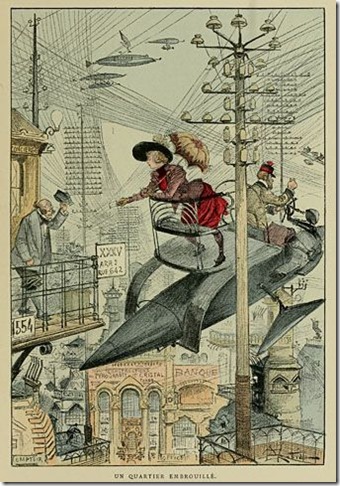

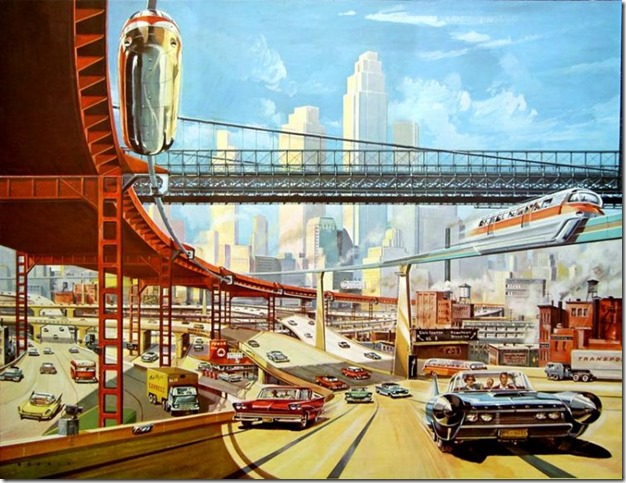

The quote captures the fact that the future is unevenly distributed in space. What it leaves out is that the future is also unevenly distributed in time. The future I see from 2016 is different from the one I imagined in 2001, and different from the horizon my parents saw in 1960, which in turn is different from the one H. G. Wells gazed at in 1933. Our experience of the future is always tuned to our expectations at any point in time.

This is a trope in science fiction and the original Star Trek pretty much perfected it. The future was less about futurism in that show than about projecting the issues of the 60’s into the future in order to instruct a 60’s audience about diversity, equality, and the anti-war movement. In that show the future horizon was a mirror that tried to show us what we really looked like through exaggerations, inversions and a bit of paint makeup.

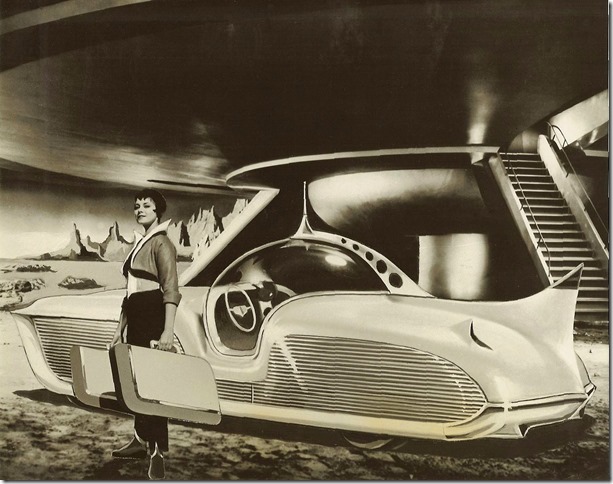

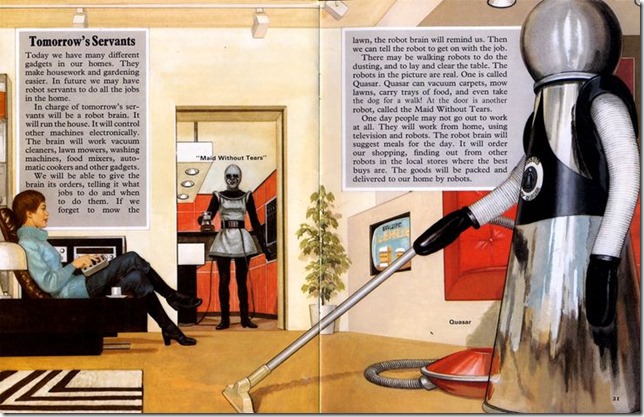

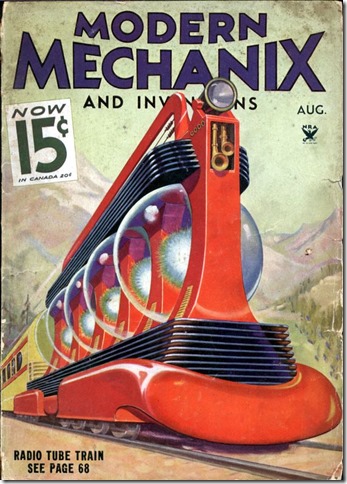

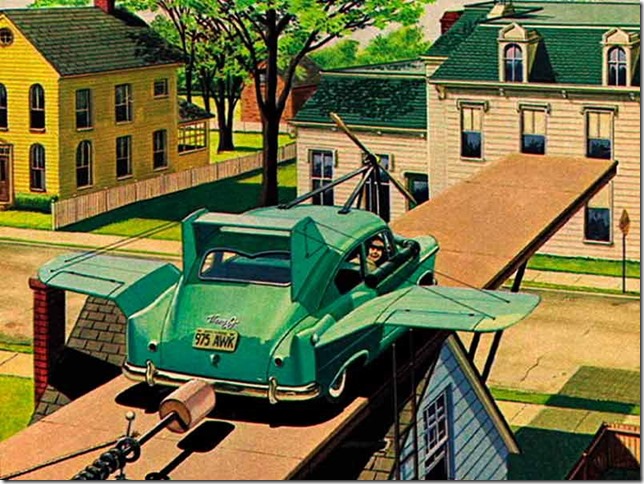

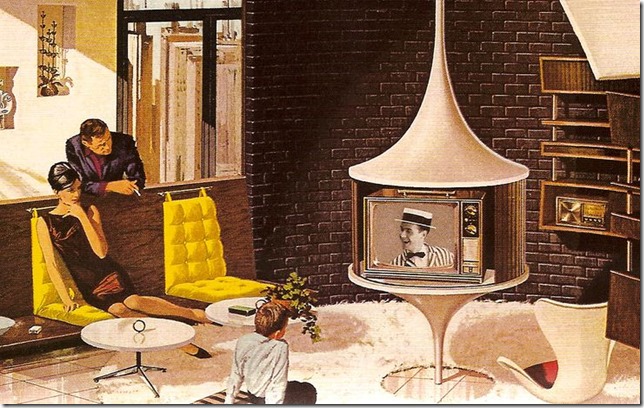

I’m grateful to Josh Rothman for introducing me to the term retrofuturism in The New Yorker, which perfectly describes this phenomenon. Retrofuturism – whose exemplars include Star Trek as well as the steampunk movement – is the quasi-historical examination of the future through the past.

The exploration of retrofuturism highlights the observation that the future is always relative to the present — not just in the sense that the tortoise will always eventually catch up to the hare, but in the sense that the future is always shaped by our present experiences, aspirations and desires. There are many predictions about how the world will be in ten or twenty years that do not fit into the experience of “the future.” Global warming and scarce resources, for instance, aren’t a part of this sense. They are simply things that will happen. Incrementally faster computers and cheaper electronics, also, are not what we think of as the future. They are just change.

What counts as the future must involve a big and unexpected change (though the fact that we have a discipline called futurism and make a sport of future predictions crimps this unexpectedness) rather than a gradual advancement and it must improve our lives (or at least appear to; dystopic perspectives and knee-jerk neo-Ludditism crimps this somewhat, too).

Most of all, though, the future must include a sense that we are escaping the present. Hannah Arendt captured this escapist element in her 1958 book The Human Condition in which she remarks on a common perspective regarding the Sputnik space launch a year previous as the first “step toward escape from men’s imprisonment to the earth.” The human condition is to be earth-bound and time-bound. Our aspiration is to be liberated from this and we pin our hopes on technology. Arendt goes on to say:

… science has realized and affirmed what men anticipated in dreams that were neither wild nor idle … buried in the highly non-respectable literature of science fiction (to which, unfortunately, nobody yet has paid the attention it deserves as a vehicle of mass sentiments and mass desires).

As a desire to escape from the present, our experience of the future is the natural correlate to a certain form of nostalgia that idealizes the past. This conservative nostalgia is not simply a love of tradition but a totemic belief that the customs of the past, followed ritualistically, will help us to escape the things that frighten us or make us feel trapped in the present. A time machine once entered, after all, goes in both directions.

This sense of the future, then, is relative to the present not just in time and space but also emotionally. It is tied to a desire for freedom and in this way even has a political dimension – if only as a tonic to despair and cynicism concerning direct political action. Our love-hate relationship to modern consumerism means we feel enslaved to consumerism yet also are waiting for it to save us with gadgets and toys in what the philosopher Peter Sloterdijk calls a state of “enlightened false consciousness”.

And so we arrive at the second most important quote for people coping with emerging technologies, also known as Clarke’s third law:

Any sufficiently advanced technology is indistinguishable from magic.

What counts as emerging changes over time. It changes based on your location. It changes based on our hopes and our fears. We always recognize it, though, because it feels like magic. It has the power to change our perspective and see a bigger world where we are not trapped in the way things are but instead feel like anything can happen and everything will work out.

Everything will work out not in the end, which is too far away, but just a little bit more in the future, just around the corner. I prepare for it by surrounding myself with gadgets and screens and diodes and notebooks, like a survivalist waiting for civilization not to crumble, but to emerge.