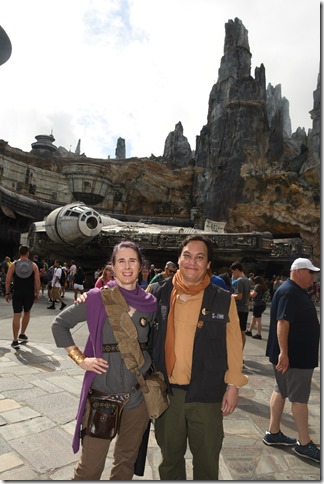

In the second week of March, I took my family to the Galactic Starcruiser at Disneyworld in Orlando, Florida, informally known as the Star Wars Hotel. The Starcruiser is a two-night immersive Star Wars experience with integrated storylines, themed meals, costumes, rides and games. For those familiar with the Disneyworld vacation experience, it should be pointed out that even though the Star Wars themed Galaxy’s Edge area in Hollywood Studios, it isn’t a resort hotel. Instead, it can best be thought of as a ride in itself.

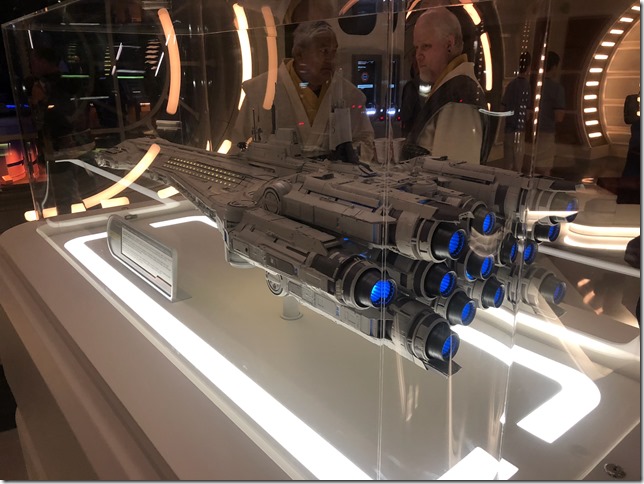

The design is that of a cruise ship, with a dining hall and helm in the “front” and an engine room in the “back”, and a space bar off of the main muster area. The NPCs and the staff never break character, but work hard to maintain the illusion that we are all on real space cruise. Besides humans, the “crew” is also staffed with aliens and robots – two essential aspects of Star Wars theming.

In line with the cruise experience, you even do a one-day excursion to a nearby alien planet. I’ve had trouble writing about this experience because it felt highly personal, lighting off areas of my child brain that were set aside for space travel fantasies. At the same time, it is also very nerdy, and the intersection of the highly nerdy and the highly personal is dangerous territory. Nevertheless, it being May 4th today, I felt I could not longer put it off.

How you do Immersion?

“Immersion” is the touchstone for what people and tech companies are calling the Metaverse. Part of this is a carry over from VR pitching, and was key to explaining why being inside a virtual reality experience was different and better than simply playing a 3D video game with a flat screen and a controller.

But the term “immersion” hides as much as it reveals. How can “immersion” be a distinguishing feature of virtual reality when it is already a built-in aspect of real reality? What makes for effective immersion? What are the benefits of immersion? Why would anyone pay to be immersed in someone else’s reality? Is immersion a way to telling a story or is storyline a component of an immersive experience?

A Russian doll aspect of the starcruiser is the “Simulation Room” which, in the storyline of the ship, is an augmented area in that recreates the climate of the planet the ship is headed toward. The room is equipped with an open roof which happens to perfectly simulate the weather in central Florida. The room also happens to be where the Saja scholars provide instruction on Jedi history and philosophy.

Space Shrimp (finding the familiar in the unfamiliar)

I’m the sort of person who finds it hard to every be present in the moment. I’m either anticipating and planning for the next day, the next week, the next few years, or I am reliving events from the past which I wish had gone better (or wish had never happened at all).

For two and a half days on this trip, I was fully captivated by the imaginary world I was living through. There wasn’t a moment after about the first hour when I was thinking about anything but the mission I was on and the details of the world I was in. I didn’t feel tempted to check my phone or know what was happening in the outside world.

An immersive experience, it seems to me, is one that can make you forget about the world in this way, by replacing it with a more captivating world and not letting go of you. I’ve been going over in my head the details of the star wars experience that make this work and I think the blue shrimp we had for dinner one night is the perfect metaphor for how Disney accomplishes immersion.

To create immersion, there can be nothing that references the outside world. The immersive experience must be self-contained and everyone in the immersive experience, from cabin boy to captain, must only reference things inside the world of the starcruiser. Fortunately Star Wars is a pre-designed universe. This helps in providing the various details that are self-referential and remind us of the world of the movies rather than the world of the world.

A great example of this is the industrial overhead shower spout and the frosted glass sliding shower door in our cabin. They are small details but harken back to the design aesthetic of the star wars movies, which contain, surprisingly, a lot of blue tinted frosted glass.

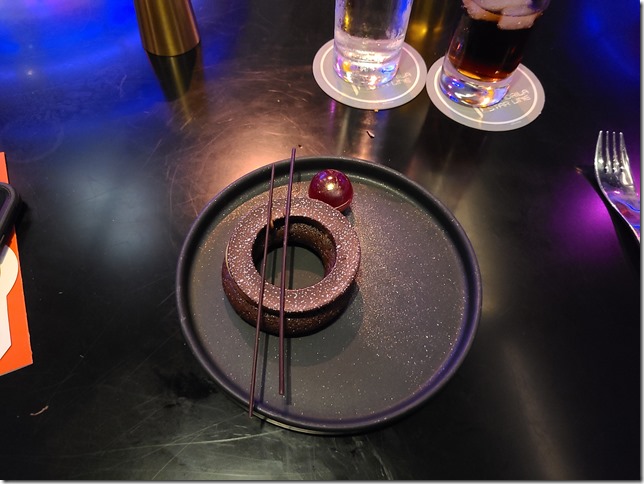

This extends to the food. All the food is themed, in a deconstructionist tour de force, to appear twisted and alien. We drank blue milk and ate bantha steaks. We feasted on green milk and salads made from the vegetation found on the planet Falucia.

And here there is a difficulty. Humans have a built-in sense of disgust of strange foods that at some point protected our ancestors from accidentally poisoning themselves. And so each item of food had to indicate, through appearance or the name given on the menu, what it was an analog of in the real world. I often found myself unable to enjoy a dish until I could identify what it was meant to be (the lobster bisque was especially difficult to identify).

What I took from this was that for immersion to work, things have to be self-referential but cannot be totally unfamiliar. As strange as each dish looked, it had to be, like the blue shrimp, analogous with something people knew from the real world outside the ship. Without these analogical connections, the food will tend to create aversion and anxiety instead of the sense of immersion intended.

One take way is that as odd as the food sometimes looked, the food analogs were always meals familiar to Americans. Things common to other parts of the world, like chicken feet or durian fruit or balut, would not go over well even though they taste good (to many people).

A second take away is that the galactic food has to be really, really good. In modern American cuisine, it is typical to provide the story behind the food explaining each ingredient’s purpose, where it comes from and how to use it in the dish (is it a salad or a garnish?). The galactic food can’t provide these value-add story points and only has fictitious ones.

In the case of the food served on the starcruiser, then, each dish has to stand on its own merits, without the usual restaurant storytelling elements that contribute to the overall sense that you are eating something expensive and worthy of that expense. Instead, each dish requires us to taste, smell, and feel the food in our mouths and decide if we liked it or not. I don’t think I’ve ever had to do that before.

World building – (decrepit futurism)

The world of Star Wars is one of decrepit futurism. It is a world of wonders in decline.

There are other kinds of futurism like the streamlined retro-futurism of the 30s and 50s or contemporary Afro-futurism. The decrepit futurism of Star Wars takes a utopic society and dirties it up, both aesthetically and morally. The original Star Wars starts off at the dissolution of the Senate marking a political decline. George Lucas doubles down on this in the prequels making this also a spiritual decline in which the Jedi are corrupted by a malignant influence and end up bringing about the fall of their own order. The story of the sequels (which is the period in which the galactic space voyage takes place) is about the difficultly and maybe impossibility of restoring the universe to its once great heights.

As beautiful and polished as all the surfaces are on the star cruiser, the ship is over 200 years old and has undergone massive renovations. Despite this, the engines continue to provide trouble (which you get to help fix). Meanwhile, the political situation in the galaxy in general and on the destination planet in particular is fraught, demanding that voyagers choose which set of storylines they will pursue. Will they help the resistance or be complicit with the First Order? Or will they opt out of this choice and instead be a Han Solo-like rogue pursuing profit amid the disorder?

The metaphysics of the Star Wars universe is essentially fallibilist and flawed – which in turn opens the way for moral growth and discovery.

The decrepit futurism of Star Wars has always seemed to me to be one of the things that makes it work best because it artfully dodges the question of why things aren’t better in a technologically advanced society. Decrepit futurism says that things once were (our preconceptions of what the future and progress entails is preserved) but have fallen from the state of grace through a Sith corruption. In falling short, the future comes down to the level where the rest of us live.

It’s also probably why Luke, in the last trilogy, never gets to be the sort of teacher we hoped he would be to Rey. The only notion we have of the greatness and wisdom of a true Jedi master comes from glimpses we get through Yoda in The Empire Strikes Back, but he is only able to achieve this level of wisdom by losing everything. Greatness in Star Wars is always something implied but never seen.

Storytelling (narrative as an organizing principle)

Much is made of storytelling and narrative in the world of immersive experiences. Some people talk as if immersion is simply a medium for storytelling – but I think it is the other way around. Immersion is created out of world building and design that distract us from our real lives. The third piece of immersion is storytelling.

But one thing I discovered on the Galactic Starcruiser is that the stories in an immersive experience don’t have to be all that great – they don’t have to have the depth of a Dostoevsky novel. Instead they can be at the level of a typical MMORPG. They can be as simple as go into the basement and kill rats to get more information. Hack a wall terminal to get a new mission. Follow the McGuffin to advance the storyline.

Narrative in an immersive experience is not magic. It’s just a way of organizing time and actions for people, much the way mathematical formulas organize the relationship between numbers or physics theorems organize the interactions of physical bodies. Narratives help us keep the thread while lots of other things are going on around us.

The main difficulty of a live theater narrative, like the one on the starcruiser, is that the multiple story lines have to work well together and work even if people are not always paying attention or even following multiple plots at the same time. Additionally, at some point, all of the storylines must converge. In this case, keeping things simple is probably the only way to go.

Crafting a narrative for immersive experiences, it seems to me, is a craft rather than an art. It doesn’t have to provide any revelations or tell us truths about ourselves. It just has to get people from one place in time to another.

The real art, of course, is that exercised by the actors who must tell these stories over and over and improvise when guests throw them a curve ball while keeping within the general outline of the overarching narrative. And being able to do this for 3 days at a time is a special gift.

Westworld vs the Metaverse (what is immersion)

Using the Galactic Starcruiser as the exemplar of an immersive experience, I wanted to go back to the question of how immersion in VR is different from immersion in reality. To put it another way, what is the difference between Westworld and the Metaverse?

There seems to be something people are after when they get excited about the Metaverse and I think it’s at bottom the ability to simulate a fantasy. Back when robots were all the rage (about the time Star Wars was originally made in the 70s) Michael Crichton captured this desire for fantasy in his film Westworld. The circle of reference is complete when one realizes that Chrichton based his robots on the animatronics at Disneyland and Disneyworld.

So what’s the difference between Westworld and the Metaverse? One of the complaints about the Metaverse (and more specifically VR) is that the lack of haptic feedback diminishes the experience. The real world, of course, is full of haptic feedback. More than this, it is also full of flavors and smells, which you cannot currently get from the Metaverse. It can also be full of people that can improvise around your personal choices so that the experience never glitches. This provides a more open world type of experience, whereas the Metaverse as it currently stands will have a lot of experiences on rails.

From all this, it seems as if the Metaverse aspires to be Westworld (or even the Galactic Starcruiser) but inevitably falls short sensuously and dynamically.

The outstanding thing about the Metaverse, though, is that it can be mass produced – precisely because it is digital and not real. The Starcruiser is prohibitively expensive dinner theater which I was able to pull off through some dumb luck with crypto currencies. It’s wonderful and if you can afford it I highly encourage you to go on that voyage into your childhood.

The Metaverse, on the other hand, is Westworld-style immersion for the masses. The bar to entry for VR is relatively low compared to a real immersive experience. Now all we have to do is get the world building, design, and storylines right.