I’ve been developing for augmented reality head-mounted displays for about eight years. I first tried the original HoloLens in 2015. Then I got to purchase a developer unit in 2016 and started doing contract work with it. Later I was in the early pre-release dev program for Magicleap’s original device, which led to more work on the HoloLens 2, Magicleap 2, and Meta Quest Pro. I continue to work in AR HMDs today.

The original community around the HoloLens was amazing. We were all competing for the same work, but at the same time, we only had each other to turn to when we needed to talk to someone who understood what we were going through. So we were all sort of frenemies, except that because Microsoft was notoriously tight-lipped with their information about the device, we helped each other out on difficult programming tricks and tricky AR UI concepts – and this made us friends as well.

In those early days, we all thought AR, and our millions in riches (oh what a greedy lot we were), were just around the corner. But we never quite managed to turn that corner. Instead we had to begin devising theories around what that corner was going to look like, what the signs would be as we approached that corner, and what would happen after we made the corner. Basically, we had to become more stringent in our analyses.

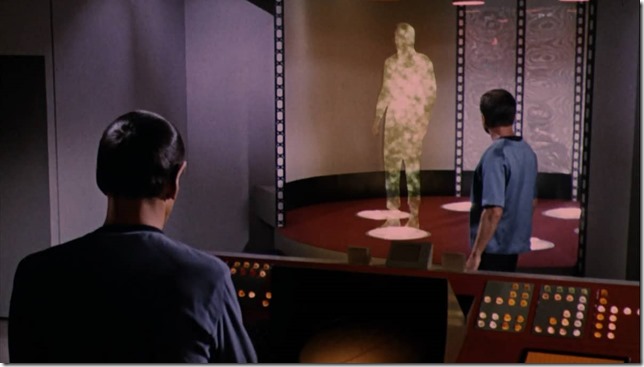

Out of this, one big idea that came to the fore was “AR Ubiquity”. This comes out of the observation that monumental technological change happens slowly and incrementally, until it suddenly happens all at once. So at some point, we believe, everyone will just be wearing AR headsets instead of carrying smartphones. (This is also known, in some quarters, as the “Inflection Point”.)

Planning, consequently, should be based less on how we get to that point, or even when it will happen; and more about how to prepare for “AR Ubiquity” and what we will do afterwards. So AR Ubiquity, in this planning model, can come in 3 years, or in 7 years, or maybe for the most skeptical of us in 20 years. It doesn’t really matter because the important work is not in divining when it will happen (or even who will make it happen) but instead in 1) what it will look like and 2) what we can do — as developers, as startups, as corporations — once it arrives.

Once we arrive at a discourse about the implications of “AR Ubiquity” rather than trying to forecast when it will happen, we are engaging with a grand historical narrative about the transformative power of tech – which is a happy place for me because I used to do research on philosophical meta-history in grad school – though admittedly I wasn’t very good at it.

“AR Ubiquity”, according to the tenets of meta-history, can at the same time both be a theory about how the world works and also a motif in a story about how we fit into the technological world. Both ways of looking at it can provide valuable insights. As a theory we want to know how we can verify (or falsify) it. As a story element, we want to know what it means. In order to discover what it means, in turn, we can excavate it for other mythical elements it resembles and draws upon. (Meta-history, it should be acknowledged, can lead to bad ideas when done poorly and probably worse ideas when it is done well. So please take this with a grain of salt (a phrase which itself has an interesting history, it is worth noting).

I can recall three variations on the theme of disruptive (or revolutionary) historical change. There’s the narrative of the apocalyptic event that you only notice once it has already happened. There’s the narrative of the prophesied event that never actually happens but is always about to. And then there’s the heralded event, which has two beats: one to announce that it is about to happen, and another when it does happen. We long thought AR would follow model A, it currently looks like it is following model B, and I hope it will turn out that we are living through storyline C. Let’s unpack this a bit.

Model A

Apocalyptic history, as told in zombie movies and TV shows, generally have unknown origins. The hero wakes up after the fateful event has already happened, often in a hospital room, and over the course of the narrative, she may or may not discover whether it was caused by a sick monkey who escaped a viral lab, or by climate change, or by aliens. There’s also the version of apocalyptic history that circulates in Evangelical Christian eschatology known as The Rapture. In the Book of Revelations (which New Yorker writer Adam Gopnik calls the most cinematic Michael Bey ready book of the Bible), St. John of Patmos has a vision in which 144,000 faithful are taken into heaven. In popular media, people wake up to find that millions of the virtuous elect have suddenly disappeared while they have been left behind to try to pick up the pieces and figure out what to do in a changed world.

In the less dramatic intellectual upheavals described in Thomas Kuhn’s The Structure of Scientific Revolutions, you can start your scientific career believing that an element known as phlogiston is released during combustion, then end it believing that phlogiston doesn’t exist and instead oxygen is added to a combusted material when it is burned (it is oxidized). Or you might start believing that the sun revolves around the earth and end up a few decades later laughing at such beliefs, to the point that it is hard to understand how anyone ever believed such outlandish things in the first place.

It’s a bit like the way we try to remember pulling out paper maps to drive somewhere new in our car, or shoving cassette tapes into our Walkmans, or having to type on physical keys on our phones – or even recalling phones that were used just for phone calls. It seems like a different age. And maybe AR glasses will be the same way . One day it seems fantastical and the next we’ll have difficulty remembering how we got things done with those quaint “smart” phones before we got our slick augmented reality glasses.

Model B

The history of waiting might best be captured by the term Millennialism, which describes both Jewish and Christian belief in the return of a Messiah after a thousand years. The study of millennialist beliefs often cover both the social changes that occur in anticipation of a Millennialist event as well as the consequent recalculation of calendars that occurs when an anticipated date has passed and finally the slow realization that nothing is going to happen, after all.

But there are non-theistic analogs to Millennialism that share some common traits such as the Cargo Cult in Fiji or later UFO cults like the Heaven’s Gate movement in the 90’s. Marxism could also be described as a sort of Millenarist cult that promised a Paradise that adherents came to learn would never arrive. One wonders at what point, in each of these belief systems, people first began to lose faith and then decided to simply play along while lacking actual conviction. The analogy can be stretched to belief in concepts like tulip bulb mania, NFTs, bitcoin, and other bubble economies where conviction eventually becomes less important than the realization that everyone else is equally cynical. In the end, it is cynicism that maintains economic bubbles and millenarist belief systems rather than faith.

I don’t think belief in AR Ubiquity is a millenarist cult, yet. It certainly hasn’t reach the stage of widespread cynicism, though it has been in a constant hype cycle over the past decade as new device announcements serve to refresh excitement about the technology. But even this excitement is making way, in a healthy manner, for a dose of skepticism over the latest announcements from Meta and Apple. There’s a hope for the best but expect the worst attitude in the air that I find refreshing, even if I don’t subscribe to it, myself.

Model C

The last paradigm for disruptive history comes in the form of a herald and the thing he is the herald for. St. John the Baptist is the herald of the Messiah, Jesus Christ, for example. And Silver Surfer is the herald for Galactus. One is a forerunner for good tidings while the other is a harbinger of doom.

The forerunner isn’t necessary for the revolutionary event itself. That will happen in any case. The forerunner is there to let us know that something is coming and to point out where we should be looking for it. And there is just something very human about wanting to be aware of something before it happens so we can more fully savor its arrival.

Model C is the scenario I find most likely and how I imagine AR Ubiquity actually happening.

First we’ll have access to a device that demonstrates an actually useable AR headset with actually useful features. This will be the “it’s for real” moment that dispels the millenarist anxiety that we’re all being taken for a ride.

The “it’s real” moment will then set a bar for hardware manufacturers to work against. The forerunner device becomes the target all AR HMD companies strive to match, once someone has shown them what works, and within a few years we will have the actual arrival of AR Ubiquity.

At this time, reviews of the Apple Vision Pro and the Meta Quest 3 suggest that either could be this harbinger headset. I have my doubts about the Meta Quest 3 because I’m not sure how much better it can be than the MQ2 and the Meta Quest Pro, especially since it has removed eye tracking, which was a key feature of MQP and made the hand tracking more useful.

The AVP, on the other hand, has had such spectacular reviews that one begins to wonder if it isn’t too good to be true.

But if the reviews can be taken at face value, then AR Ubiquity, or at least a herald that shows us it is possible, might be closer than we think.

I’m just proposing a small tweak to the standard model of how augmented reality headsets will replace smartphones. We’ve been assuming that the first device that convinces consumers to purchase AR headsets will also immediately set off this transition from one device category to the other. But maybe this is going to occur in two steps. First a headset will appear that validates the theory that headsets can replace handsets. Then a second device will rotate the gears of history and lead us into this highly anticipated new technological age.