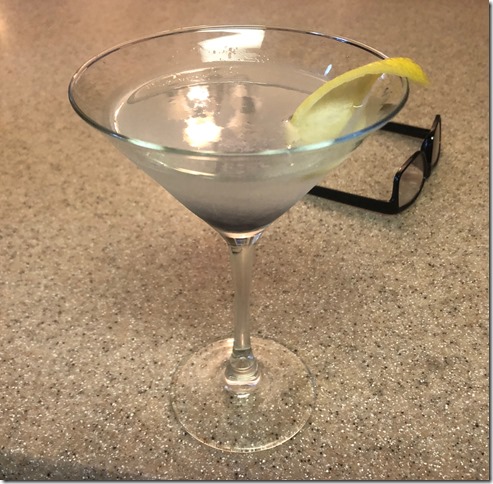

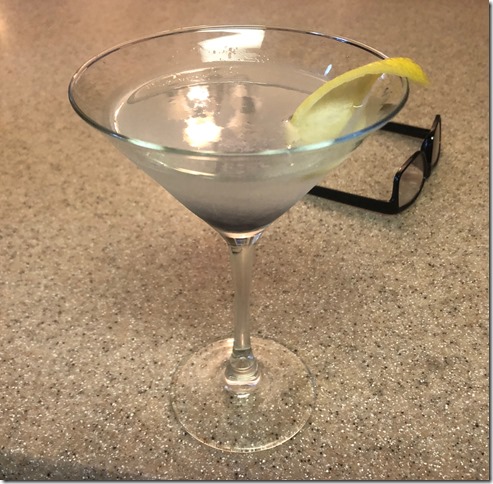

This is the Aviation cocktail. It is one of the earliest recorded cocktails of the 20th century. Just sourcing the ingredients can be a feat in itself.

- 2 oz gin

- 1/2 oz lemon juice

- 1/4 oz maraschino liqueur

- 1/4 oz creme de violette

Shake with ice and pour into a martini glass. Garnish with a lemon twist or a maraschino cherry. There is some controversy about the creme de violette. Some people leave it out altogether, on the theory that modern versions of the liqueur are inferior to that used in the original drink. Some throw it in with the rest of the ingredients in the shaker, which creates a very purple drink. I like to add it over a spoon after pouring the glass so it is in a separate layer, creating a morning dawn with clouds effect, which is how the drink originally got its name.

The disputes over the right way to make an Aviation follow a long term (or long form) mode of thought. This is unusual and increasingly rare. Typically we make short term decisions, and this has been blamed many of the follies we face today.

Stock market investment is meant to be a long term matter but many of the disasters that occur in the market seem to occur when people treat it as a short form (i.e. gambling) metier. There was a time, as with the characters in a Jane Austen novel, when a person’s worth was calculated based on a 5% return on investments. Mr. Darcy was worth 10,000 pounds a year, which meant he had an endowment of 200,000 pounds. 10,000 pounds a year put Mr. Darcy in the top 1% of British incomes at the time. His 10,000 pounds is equivalent to around £450,000 today, according to a quick unverified Google search I just did. His modern equivalent, I imagine, would consequently be Jared Kushner, not Colin Firth, which makes Ivanka Trump our Elizabeth Bennett!

Okay. Enough of that. Short term thinking vs. long term thinking. That is the current topic.

I once had a manager to whom I expressed my concerns that the path we were on in building a software product simply wouldn’t work. There was no audience for it. I was concerned that my manager was hiding information from the CEO of the company and that this would lead to disaster down the road, including but not limited to everyone losing their jobs. My manager calmly told me with a smile that this was something I shouldn’t worry about and that if his strategy didn’t work, it was his job that would be forfeit, not mine.

I think he was sincere in saying this, to the extent any manager is capable of sincerity (I’ve known a few), but the problem was that this was short term thinking. In the short term, he was confident that what he was saying was true. Later, however, adverse circumstances led to a shortfall in income and I moved on to other employment while he continued doing internal pitches in order to get more money for his project. He of course forgot about any claims he had made previously.

There are several lessons that can be drawn from this. The first is never to trust management. They are not on your side. Their job is to figure out how to get you to further their own goals.

The second is that something said can be true in the short term but not true in the long term. In the short term, people will say whatever gets them through to the end of the meeting they are in. This is what we also call a pragmatic attitude.

Statements concerning actions that are true over the long term are actually called “ethics”. When someone claims they will do something, and perhaps believe it, but after a few days or a few weeks, abandons that promise, then they are being unethical. If the keep to their word over the long term, they are being ethical. A characteristic of people who keep their word over the long term is that they are thoughtful about what they say and what they promise.

Even the beliefs we hold can be ethical or unethical in this way. I was once serving jury duty in a case that was pretty fun – about which I can’t really say anything. Most of the jury was inclined one way while two were inclined another. At the end of the deliberations, one of the hold outs was eventually ready to change his vote because he had a party he wanted to go to that night. So it was down to the fore-person. She made multiple arguments about how it was possible that the person on trial may not have done what he was accused of. And honestly her intentions were good. She was concerned about the three-strikes mandate that at the time would have given the defendant an excessive punishment, and many juries at the time were struggling with the notion of jury nullification in cases where they felt the criminal justice system itself was unfair. It occurred to me to ask her, out of curiosity, whether she believed what she was saying.

After which there was a long pause of at least a minute and maybe more. She then announced that she was changing her vote and we returned to the courtroom to announce our verdict.

“Is that true” is a powerful question, I discovered that day.

In life, we all say things that sound good at the moment. When I supported pitches to the client while working at a digital agency, this was what we did every day. We said things that sounded good. Strangely, we always believed what we were saying when we said it. Following the George Costanza rule, it isn’t a lie if you believe it.

But what we believe in the moment isn’t the same thing as an ‘ethical belief’. It can be blamed on social media, the lowering of public discourse, the long term effects of Trumpism, but it feels like people no longer believe or speak ethically anymore. There is no sense that the things we say should be true or that the promises we made should be kept. It’s all just words …

And words can destroy lives, markets, norms, social bonds and potentially great nations. My hope for the Biden presidency is that we will finally have ethical beliefs, again.