One of the great burdens and pleasures of being at home is filling a lot of down time with streaming content. I currently stream from Amazon Prime, Netflix, Comcast, Disney, Shudder, Criterion Channel, Crunchyroll, Hulu, Master Class and HBO Max. Of these, Amazon Prime seems to be the least curated. You find the weirdest things.

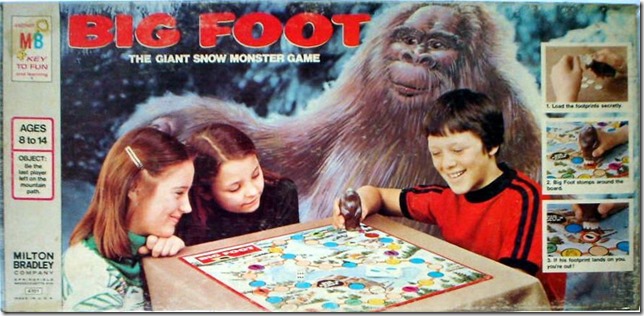

Prime has a lot of Sasquatch movies. My early fascination with Bigfoot starts with the Leonard Nimoy In Search of … series and continues through Harry and the Hendersons, multiple The X-Files episodes, Abominable (the bigfoot movie based on Alfred Hitchcock’s Rear Window) and more recently The Man Who Killed Hitler and then the Bigfoot starring Sam Elliott and Aidan Turner.

None of this had prepared me, however, for the experience that is Bigfoot Tales of Darkness. Here is the irresistible synopsis provided by Amazon:

This is a series of tales of Bigfoot, of a mythical creature from heaven that once was a arch angel named Lucifer has come to earth and man knows him as Bigfoot. As he kills and rampages humans through all the tales in this story.

I couldn’t get through more than ten minutes of it. The film seems to be pieced together out of stock video purchased online with some homemade electronic music layered over the top.

But I still want to give it the attention it may not deserve because it is so crazy and someone somewhere, using the tools available to them, went to the trouble of making a movie about Bigfoot being the devil and somehow got it onto Amazon Prime. Plus I have lots of extra non-commuting time these days.

There’s a theory of literature called Reader-response criticism that fits well into the way we currently consume media. It rejects modernist theories of authorial intent and concerns itself more with the experience of the reader. This was a precursor of the “death of the author” movements that came in the 80’s.

In our own times, the way people access media and the rise of cult followings has dramatically changed the way films are created, marketed and distributed. Audiences are balkanized in such a way that content marketed to small groups and genre fans can be highly profitable and can even afford to alienate large swathes of people. This is in contrast to massive budget superhero films that can only achieve profitability by killing on opening day as well as in overseas markets (esp China) and then in the cable, streaming and DVD aftermarkets as well as product tie-ins and merchandising.

Following some of Umberto Eco’s ideas, this made me wonder if I could make myself an ideal reader for this movie. An audience of one.

To accomplish this (and overcome my physical response to the first 10 minutes of Bigfoot Tales of Darkness, a combination of lethargy and nausea) I need to put it in a different intellectual context.

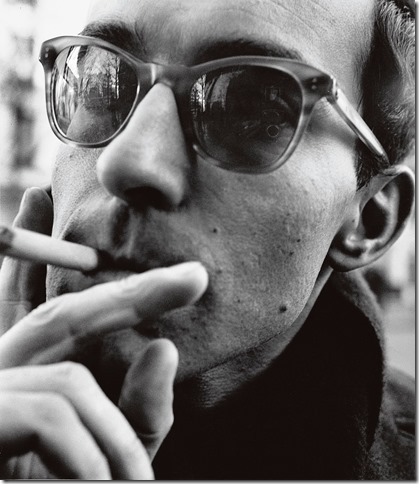

Because it might be some kind of highly experimental film that plays on genres and narrative structure, eschewing actors for stock video clips, I decided the avant-garde French film director Jean-Luc Godard might be a good reference for understanding (or creating an understanding) of what the ideal author of this Bigfoot movie is trying to say.

Godard’s last two films, in particular, have adopted a bricolage style of film-making, clipping together images and fragments, using both high quality film and low quality video, with often confusing sound editing that breaks up the continuity instead of tying it together like a normal movie score would do.

Over the next week I plan to watch and report on Godard’s 2014 award-winning film Goodbye to Language, about a couple’s breakup interspersed with shots of a dog playing, and his 2018 film The Image Book about the misrepresentation of Arab culture in Western movie making.

They both have poor reviews on IMDB. Critics, amirite?

I’ll follow this with a fair attempt to assess Bigfoot Tales of Darkness on its own terms.