In a 2010 piece for The New Yorker called Painkiller Deathstreak , the novelist Nicholson Baker reported on his efforts to enter the world of console video games with forays into triple-A titles such as Call of Duty: World at War, Halo 3: ODST, God of War III, Uncharted 2: Among Thieves, and Red Dead Redemption.

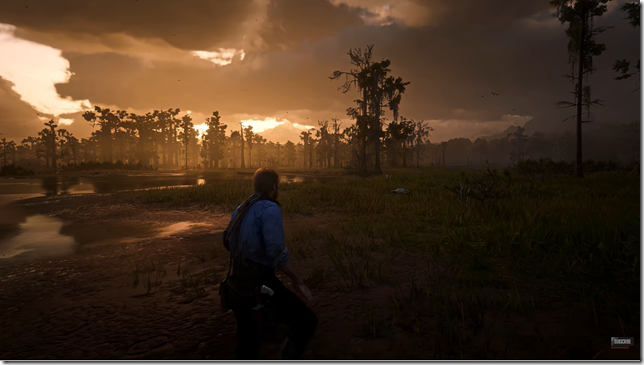

“[T]he games can be beautiful. The ‘maps’ or ‘levels’—that is, the three-dimensional physical spaces in which your character moves and acts—are sometimes wonders of explorable specificity. You’ll see an edge-shined, light-bloomed, magic-hour gilded glow on a row of half-wrecked buildings and you’ll want to stop for a few minutes just to take it in. But be careful—that’s when you can get shot by a sniper.”

In his journey through worlds rendered on what was considered high-end graphics a decade ago, Nicholson discovered both the frustrations of playing war games against 13 year olds (currently they would be old enough to be stationed in Afghanistan) as well as the peace to be found in virtual environments like Red Dead Redemption’s Western simulator.

“But after an exhausting day of shooting and skinning and looting and dying comes the real greatness of this game: you stand outside, off the trail, near Hanging Rock, utterly alone, in the cool, insect-chirping enormity of the scrublands, feeling remorse for your many crimes, with a gigantic predawn moon silvering the cacti and a bounty of several hundred dollars on your head. A map says there’s treasure to be found nearby, and that will happen in time, but the best treasure of all is early sunrise. Red Dead Redemption has some of the finest dawns and dusks in all of moving pictures.”

I was reminded of this essay yesterday when Youtube’s algorithms served up a video of Red Dead Redemption 2 (the sequel to the game Nicholson wrote about) being rendered in 8K on an NVidia 3090 graphics card with raytracing turned on.

The encroachment of simulations upon the real world, to the point that they not only look as good as the real world (real?) but in some aspects even better, has interestingly driven the development of the sorts of AI algorithms that serve these videos up to us on our computers. Simulations require mathematical calculations that cannot be done as accurately or as fast on standard CPUs. This is why hardcore gamers pay upwards of a thousand dollars for bleeding edge graphics cards that are specially designed to perform floating point calculations.

These types of calculations, interestingly, are also required for working with large data sets for machine learning. The algorithms that steer our online interests, after all, are just simulations themselves, designed to replicate aspects of the real world in order to make predictions about what sorts of videos (based on a predictive model of human behavior honed to our particular tastes) are most likely to increase our dwell time on Youtube.

Simulations, models and algorithms at this point are all interchangeable terms. The best computer chess programs may or may not understand how chess players think (this is a question for the philosophers). What cannot be denied is that they adequately simulate a master chess player that can beat all the other chess players in the world. Other programs model the stock market and tune them back into the past to see how accurate they are as simulations, then tune them into the future in order to find out what will happen tomorrow – at which point we call them algorithms. Like memory, presence and anticipation for us meatware beings, simulation, model and algorithm make up the false consciousness of AIs.

Simulacra and Simulation, Jean Baudrillard’s 1981 treatise on virtual reality, opens with an analysis of the George Luis Borges short story On Exactitude in Science, about imperial cartographers who strive after precision by creating ever larger and larger maps, until the maps eventually achieve a one-to-one scale, becoming exact even as they overtake their intended purpose.

“The territory no longer precedes the map, nor survives it. Henceforth, it is the map that precedes the territory – precession of simulacra – it is the map that engenders the territory and if we were to revive the fable today, it would be the territory whose shreds are slowly rotting across the map. It is the real, and not the map, whose vestiges subsist here and there, in the deserts which are no longer those of the Empire, but our own. The desert of the real itself.”

I was thinking of Baudrillard and Borges this morning when, by coincidence, Youtube served up a video of comparative map sizes in video games. Even as rendering versimilitude has been one way to gauge the increasing realism of video games, the size of game worlds has been another. A large world provides depth and variety – a simulation of the depth and happenstance we expect in reality – that increases the immersiveness of the game.

Space exploration games like No Man’s Sky and Elite Dangerous attempt to simulate all of known space as your playing ground, while Microsoft’s Flight Simulator uses data from Bing Maps to allow you to fly over the entire earth. In each case, the increased size is achieved by surrendering on detail. But this setback is temporary, and over time we will be able to match the extent of these simulations with detail, also, until the difference between the real and the model of the real is negligible.

One of the key difficulties with VR adoption (and to some extent the superiority of AR) is the falling anxiety everyone experiences as they move around in virtual reality. The suspicion that there are hidden objects in the world that the VR experience does not reveal to us prevents us from being fully immersed in the game – except in the case of the highly popular horror genre VR games in which inspiring anxiety is a mark of success. As the movements continue to both increase the detail of our simulations of the real world – to the point of simulating the living room sofa and the kitchen cabinet – and expand the coverage of our simulations across the world so there is no surveillable surface that can escape the increasing exactness of our model, we will eventually overcome VR anxiety. At that point, we will be able to walk around in our VR goggles without ever being afraid of tripping over objects, because there will be a one-to-one correspondence between what we see and what we feel. AR and VR will be indistinguishable at that exacting point, and we will at last be able to tread upon the sands of the desert of the real.