It is a commonplace that humor resists translation. This was Pevear and Volokhonsky’s conceit when they came out with a new translation of The Brothers Karamazov in 1990, which they claimed finally brought across (successfully, I think) the deep humor of Dostoevsky’s masterpiece. While accuracy is the goal in most translation efforts, to hold to accuracy when translating humor unavoidably leaves much untranslated. Thus in translating Lewis Caroll into Russian, Vladimir Nabokov chose to replace English wordplay with completely different puns sensible only to the Russian speaker, all the better to capture the flavor of Caroll’s humor.

A former colleague at the infamous Turner Studios has posted the following joke to his blog, which I must admit I cannot decipher:

Yet I know it is a joke, because he adds the following gloss to the image:

Let the hilarity ensue. Someone put up a site where you can build your own World of Warcraft talent trees. The priest one made me laugh, since it’s twoo, it’s twoo.

What is one required to know in order to decipher this particular joke? Initially, of course, one must know that this is an artifact of the online game World of Warcraft, which is a complex virtual world people pay a monthly fee in order to gain access to. Next, the artifact is a “talent tree”, which describes different abilities people can gain through accruing time in the virtual world. The various talents form a tree in the sense that one must gain lower level talents before one may achieve the higher talents, and while the low level talents form a broad base, there are fewer high level talents to choose from when one gets to the top. The choice of talents one chooses to acquire, in turn, determines what sort of person one is in the virtual World of Warcraft.

This is the formal aspect of the talent tree. In order to understand the hilarity of this particular talent tree, however, one must further understand the pictorial vocabulary used to represent talents in this tree, a task requiring a Rosetta stone of sorts. The use of pictures to tell stories is old, and certainly predates any written languages, with exemplars such as the cave drawings at Lascaux. Long after the advent of written languages, images continued to exert a central role in the telling of stories and the transmission of culture in societies where the majority of people were illiterate. It was even the main way that Christianity promulgated its teachings to the masses, and the eventual eclipse of the central role of images in religious life by way of the Protestant Reformation can be seen as a direct result of the emphasis placed on reading the Bible for oneself, and hence the importance of literacy.

Beyond pratfalls and scatology, I’m not sure that pictures without words are a particularly effective means of transmitting humor. The talent tree for the priest represented above has less to do with cave paintings at Lascaux than with the Renaissance emblem book tradition, which does attempt to treat images as language, and reached its height of artistic expression with the HYPNEROTOMACHIA POLIPHILI. The traditional emblem book was made up of a series of 100 or so images that were explicated with poems and allegories. What sets them apart from instructive religious images is that they require a high level of literacy in order to read and enjoy, whereas religious images during the same period were particularly useful for the illiterate. In some cases, due to the expense of printing woodcuts, emblem books would even forgo actual images and instead would include mere descriptions of the emblems being explicated. Implicit in all of this, however, was the understanding that whatever could be said about the emblems was originally and overabundantly expressed in the images themselves, and that the accompanying text merely offered a glimpse into their hidden meanings.

Athanasius Kircher, the 17th century polymath, pursued a similar approach toward deciphering Egyptian hieroglyphs. An interesting website dedicated to and to some extent influenced by his work can be found here. Following the work of 19th century Egyptologists like Jean-François Champollion, we know today that Egyptian hieroglyphs alternately represent either phonetic elements or words, depending on how they are used. In the case of cartouches, the series of symbols often found on monuments and usually placed in an oval in order to set them apart, hieroglyphs were exclusively a phonetic alphabet used to spell out the personal names of Egyptian dignitaries. For Kircher, however, they represented a language of images which, if not actually magical, were at least possessed of superabundant and secret meaning. Kircher sought transcendence in his efforts to cull meaning from cartouches. How far he fell short can be gathered from this gloss by Umberto Eco in The Search For The Perfect Language:

>Out of this passion for the occult came those attempts at decipherment which now amuse Egyptologists. On page 557 of his Obeliscus Pamphylius, figures 20-4 reproduce the images of a cartouche to which Kircher gives the following reading: ‘the originator of all fecundity and vegetation is Osiris whose generative power bears from heaven to his kingdom the Sacred Mophtha.’ This same image was deciphered by Champollion (Lettre a Dacier, 29), who used Kircher’s own reporductions, as ‘AOTKRTA (Autocrat or Emperor) sun of the son and sovereign of the crown, Caesar Domitian Augustus)’. The difference is, to say the least, notable, especially as regards the mysterious Mophtha, figured as a lion, over which Kircher expended pages and pages of mystic exegesis listing its numerous properties, while for Champollion the lion simply stands for the Greek letter lambda.

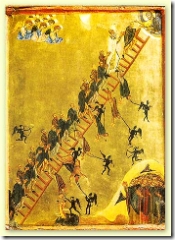

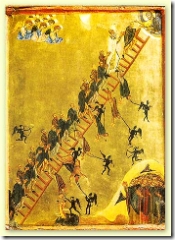

Whereas Kircher’s search for transcendence requires great learning, the icon to the right, of the Ladder of Divine Ascent, is accessible to the unliterate. Most icons in the Eastern Orthodox tradition are of saints, and are used in prayer to the saints. Icons that depict stories, such as this icon, are somewhat rare, though there is evidence that this was in fact the prior tradition, and the earliest Christian images, found in the catacombs of Rome, typically depict stories from the Bible. The icon of the Ladder of Divine Ascent is based on the ladder described by John Climacus in the 7th century book of the same name, and the Orthodox saint can in fact be found at the lower left corner of the image. Climacus, in turn, borrowed his ladder from the image of a ladder that Jacob dreamed about, a ladder extending from earth to heaven. In this icon, Christ stands at the top of the ladder, welcoming anyone who can make the full ascent. At the bottom are monks lining up to attempt the climb, while in between we see ascetics being diverted, distracted, and pulled off of the ladder by demonic beings. The message is fairly straight forward. Transcendence and salvation are possible, but very difficult. The ladder represents the journey, but also the mediation required to ascend from the cthonic to the celestial.

Whereas Kircher’s search for transcendence requires great learning, the icon to the right, of the Ladder of Divine Ascent, is accessible to the unliterate. Most icons in the Eastern Orthodox tradition are of saints, and are used in prayer to the saints. Icons that depict stories, such as this icon, are somewhat rare, though there is evidence that this was in fact the prior tradition, and the earliest Christian images, found in the catacombs of Rome, typically depict stories from the Bible. The icon of the Ladder of Divine Ascent is based on the ladder described by John Climacus in the 7th century book of the same name, and the Orthodox saint can in fact be found at the lower left corner of the image. Climacus, in turn, borrowed his ladder from the image of a ladder that Jacob dreamed about, a ladder extending from earth to heaven. In this icon, Christ stands at the top of the ladder, welcoming anyone who can make the full ascent. At the bottom are monks lining up to attempt the climb, while in between we see ascetics being diverted, distracted, and pulled off of the ladder by demonic beings. The message is fairly straight forward. Transcendence and salvation are possible, but very difficult. The ladder represents the journey, but also the mediation required to ascend from the cthonic to the celestial.

I find the metaphor of the ladder striking because 1) it is man-made, and 2) it is something that one steps off of when one reaches the top. These two features explain why the talent tree depicted above could never be a talent ladder, even though both are things that one climbs. The tree is something made of the same earthly material that it grows out of. It reaches for the sky, but because it is not truly a mediator, it cannot allow one to step off of it, and in fact the higher one climbs, the less stable one’s purchase is. Just as a pier is a disappointed bridge, as James Joyce indicated, a tree is a disappointed ladder. It goes nowhere.

This, I take it, is the humor inherent in the talent tree above. The talent tree provides a semblance of movement upwards, but ultimately disappoints. It always provides more, but the more turns out to be more of the same. For an interesting unpacking of this phenomenon, one could do worse than read this cautionary blog about the dangers of playing World of Warcraft:

>60 levels, 30+ epics, a few really good “real life” friends, a seat on the oldest and largest guild on our server’s council, 70+ days “/played,” and one “real” year later…

…

It took a huge personal toll on me. To illustrate the impact it had, let’s look at me one year later. When I started playing, I was working towards getting into the best shape of my life (and making good progress, too). Now a year later, I’m about 30 pounds heavier that I was back then, and it is not muscle. I had a lot of hobbies including DJing (which I was pretty accomplished at) and music as well as writing and martial arts. I haven’t touched a record or my guitar for over a year and I think if I tried any Kung Fu my gut would throw my back out. Finally, and most significantly, I had a very satisfying social life before.

…

These changes are miniscule, however, compared to what has happened in quite a few other people’s lives. Some background… Blizzard created a game that you simply can not win. Not only that, the only way to “get better” is to play more and more. In order to progress, you have to farm your little heart out in one way or another: either weeks at a time PvPing to make your rank or weeks at a time getting materials for and “conquering” raid instances, or dungeons where you get “epic loot” (pixilated things that increase your abilities, therefore making you “better”). And what do you do after these mighty dungeons fall before you and your friend’s wrath? Go back the next week (not sooner, Blizzard made sure you can only raid the best instances once a week) and do it again (imagine if Alexander the Great had to push across the Middle East every damn week).

The burden of Sisyphus is a perennial staple of humorists, and not a tragedy at all. Consider the most famous Laurel and Hardy short, The Music Box, in which the conceit of the whole film is the two bunglers trying to move a piano to a house on top of a hill. Perhaps the most iconic example of this sort of humor is Nigel’s amplifier from This Is Spinal Tap, which “goes to eleven”. For Nigel, eleven is a transcendent level of amplification, while for the mock interviewer, it is just one more number. Why not just re-calibrate the amplifier and make ten eleven? Nigel believes that eleven transforms the amplifier into a ladder, whereas the audience recognizes that it is just a tree.

I am at a point in my life where I see trees and ladders everywhere. For instance, the constant philosophical debates around the mind-body problem can be broken down into a simple question about whether consciousness is a tree or a ladder. If consciousness is the complex accumulation of basically simple brain processes, then it is a tree. If aggregating various physical processes never can achieve true consciousness, then consciousness is a ladder. And then from these two basic theses, we can arrive at all the other combinations of mind-body solutions, for instance that it is a tree that thinks it is a ladder, or a ladder that thinks it is a tree, or that ladder and tree are simply two equivalent modes of describing the same phenomenon, depending possibly on whether one is in fact a tree or a ladder.

Science fiction plots, in turn, can be broken down into two types: those in which ladders pretend to be trees, and those in which trees pretend to be ladders. Virtual worlds, finally, are the culmination of a historical weariness over these problems, and a consequent ambivalence about whether trees and ladders make any difference, anymore. For those who have chosen to forgo the search for ladders, virtual worlds provide a world of trees, which simulate the experience of climbing ladders — virtual ladders, so to speak.

Having had several years of success, Blizzard, the makers of World of Warcraft, have recently released a new expansion to their online world called The Burning Crusade. Whereas up to this point, players have been limited to a maximum level of 60, those who buy The Burning Crusade will have that ceiling lifted. With The Burning Crusade, World of Warcraft goes to level 70.

Whereas Kircher’s search for transcendence requires great learning, the icon to the right, of the

Whereas Kircher’s search for transcendence requires great learning, the icon to the right, of the